Julia Counts for PL Researchers¶

Julia is an interesting programming language.

It’s fast, expressive, when keeping a dynamic programming language.

From the perspective of Programming Language, I feel like to give some short introductions of Julia, in this structure:

- Expressiveness

- LISP macro system

- Type system(think why I say “type system” for a dynamic language?)

- Staging

- Advantages as a codegen backend

- Everything is expression

- HPC: easy GPU/SIMD interfaces

- Capability of generating LLVM IR/native ASM

Expressiveness¶

Julia is likely to be the most expressive dynamic programming language.

It has LISP macros, with which can you manipulate your program in AST level.

Its low level IR(between AST and LLVM) is available to users, hence you could re-compile your functions, and change its behaviors.

It has a type system, which at least get rid of some unsoundness examples shown in Java. Specifically, it implements the “right” covariance, which works well with parametric types without suffering from the potentially incorrect coercions.

Let’s see the macro part first.

Julia ASTs are symbolic expressions(s-expressions), and available by using the macro syntax.

macro identity_process(code)

code

end

macro get_ast(code)

QuoteNode(code)

end

x = @identity_process 1 + 1

println(x) # 2

y = @get_ast 1 + 1

println(y) # 1 + 1

dump(y)

# Expr

# head: Symbol call

# args: Array{Any}((3,))

# 1: Symbol +

# 2: Int64 1

# 3: Int64 1

Syntactically constructing an AST node is allowed, by using quotations.

expr1 = quote

x = 1

y = 1

end

expr2 = :(x + y)

Further, the scope issues of macro system are solved by the support of hygiene and unhygiene. In a macro function, i.e, a function defined by leading keyword macro, if you return a esc(code), the returned AST is unhygienic.

Q: What is the hygiene of macro?

A: The symbols used in the processed AST will not interact with the scope of macro callsites. Hence, the scope of macro callsites will not change, the binding, reading or writing of symbols are separate from the callsite.

Q: What is the unhygiene of macro?

A: You can refer the symbols from macro callsites. Hence, you can use macros to add new symbols, change value of a symbol, and so on.

This design permits the full featured use of LISP macros.

Next, let us focus on the type system.

Julia is strongly typed, hence you cannot coerce the type of a datum unlimitedly.

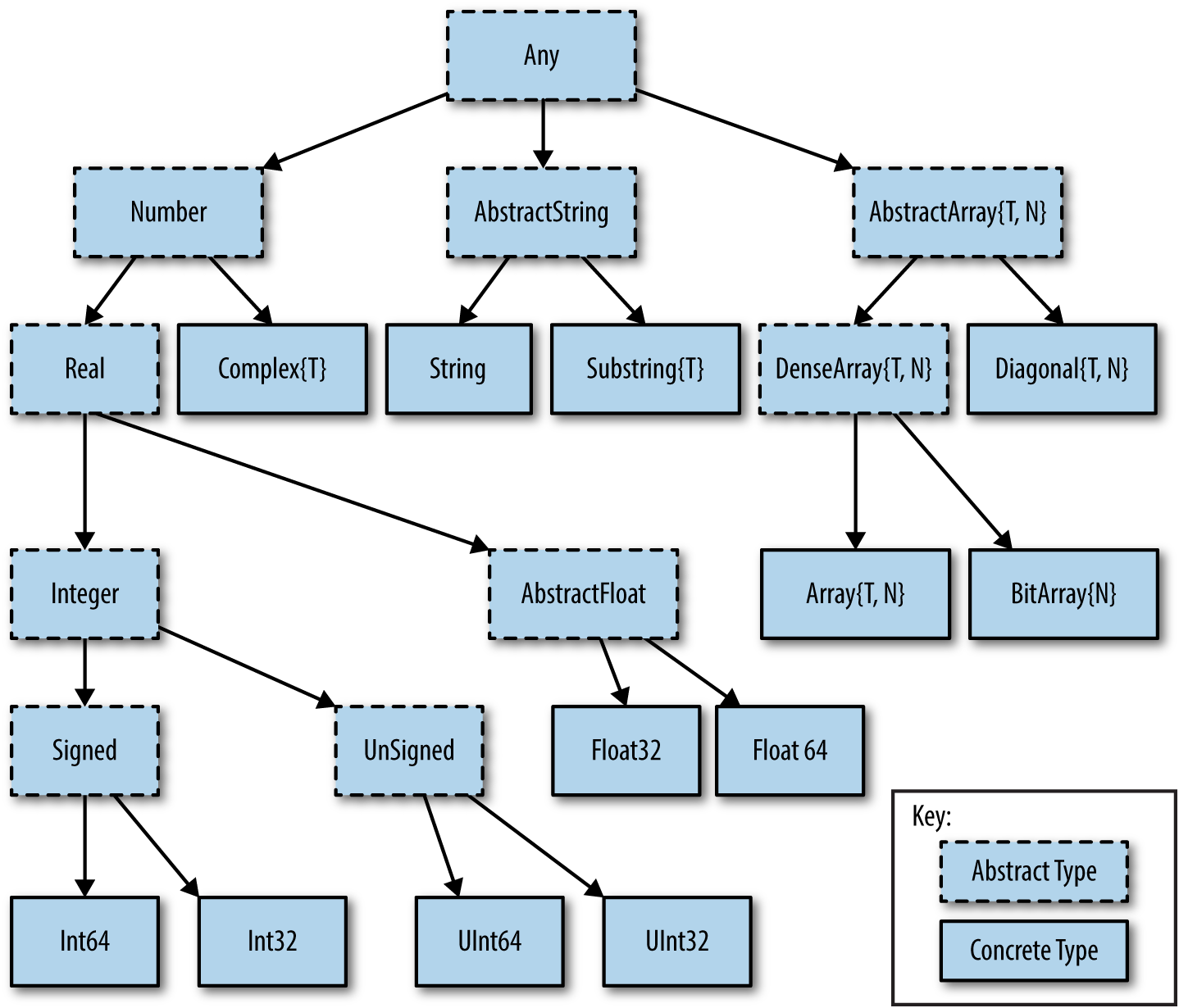

The type hierarchy is relatively clean.

You can upcast the type to its super type, and runtime type information will be stored as well. When downcasting the type to a specific one, type assertions will be performed on the stored runtime type information, to check its validity.

This mechanism contributes to Julia’s type safety.

Covariance in Julia looks pretty good

function F(arg :: Vector{a}) where a <: Number

a

end

F([1, 2, 3]) # => Int

F(["2", "3"]) # => string

Because in Julia, covariance successfully gets distinguished from heterogenous abstract types.

function G(arg :: Vector{Number})

# or function F(arg :: Vector{a where a <: Number})

end

G([1, 2]) # error!

Above codes report an error:

ERROR: MethodError: no method matching F(::Array{Int64,1})

Closest candidates are:

F(::Array{Number,1}) at ...

Why, isn’t a vector of integers a vector of numbers?

May not, because there’re ambiguities. When we say “a vector of numbers”, are we meaning “a vector of any numbers”, or “a vector of some kind of numbers”?

In Julia, things get distinguished.

A vector of some kind of numbers is Vector{a} where a <: Number, or Vector{<:Number}, which is the correct “generic” type.

A vector of any numbers is, Vector{a where a <: Number}, or Vector{Number}, which is heterogenous.

Besides, “some kind of numbers” belongs to “any numbers”, so Vector{Number} is an instance of Vector{<:Number}, and the converse doesn’t hold.

Additionally, Julia provides us with a type system including runtime type representations and useful operations, which are quite handy.

sort(

# T[a, b, c] is a vector of type Vector{T}

Type[

Vector{a} where a <: Integer,

Vector{Int},

Vector{a} where a <: Number

],

lt=(<:)

)

We got

3-element Array{Type,1}:

Array{Int64,1}

Array{a,1} where a<:Integer

Array{a,1} where a<:Number

Vector{a} is an alias for Array{a, 1}.

As for a higher level interface for user programming, Julia has parametric functions. It’s called multiple dispatch, which provides ad hoc polymorphisms, including virtual dispatch(runtime) and static dispatch(compile time).

f(x::Int) = x + 1

f(x::String) = x

Staging¶

I love staging techniques, and staging in Julia is very handy and powerful. Julia integrates quite a few partial evaluation techniques, and I love their staging implementation the most.

Julia has a special utility for runtime code generation, called “generated functions”. In the early stage and the first edition of Julia paper, it’s called “staged functions”.

It’s amazing because it does zero-cost runtime code generation. Yes, zero-cost.

An example shows something probably only available in Julia.

For instance, we can automatically generate functions which summary all integer elements of tuples of any sizes.

@generated function sum_ints(x::T) where T <: Tuple

tuple_element_types = T.parameters

i = 1

code = 0

for each in tuple_element_types

if each == Int

code = :($code + x[$i])

end

i += 1

end

code

end

Above code eliminates the runtime type checking of tuple elements. sum_ints generates a specialized implementation for all distinct argument types, if used/invoked.

Advantages:

- The generation for each argument type happens once only, managed by compiler

- You don’t have to control when and where to generate it yourself.

- After performing the code generation, it may trigger recompilation of existing functions, to inline more

Disadvantage:

- space-consuming

- difficult in re-generation

- The generator code (used to build the AST from the argument types) cannot call functions or methods which are defined after the generated function is defined. (from this post)

Advantages as a codegen backend¶

Julia is pretty suitable as a codegen backend.

Firstly, syntactically, language constructs in Julia are all expressions.

Expressions make things easier for lowering higher level program representations to lower IRs.

Say, if we have some abstract syntaxes, in OCaml notations, we write

type exp =

| Assignment of name * exp

| BlockExpr of exp list

So, BlockExpr is a suite of expressions, whose result is the last expression inside the block.

This just cannot get implemented trivially(I mean “directly syntax mapping without control flow analysis”).

Thus, when targeting ordinary C(C99), or Python(lower than 3.8), or older Java(prior before Java8), block expressions are difficult to translate/compile.

Julia suffices, with this wise language design.

P.S: I will never forget how awful it is when I’m compiling T-SQL to Python.

Secondly, I think you’d like to use those fashionable and practical HPC stuffs, like accelerating by GPU or SIMD.

Julia can easily access native world, with many convenient encapsulations in different levels through hardwares to softwares.

For SIMD, things are easy because SIMD support is builtin.

SIMD accelerates loops in this way:

function vector_add2_simd(arr)

n = length(arr)

@simd for i in 1:n

@inbounds arr[i] += 2

end

end

@inbounds is very nice, which eliminates array boundary checking. Just low level enough in such a high level language.

For GPU accelerations, you have many choices.

So far, CuArray implemented by JuliaGPU organization is pretty good.

using CuArrays

cuarr = cu([1, 2, 3])

cuarr .+= 2 # all element do inplace add 2, with GPU

cuarr .*= 2 # all element do inplace multiply 2, with GPU

. means broadcast in Julia, functions can also use broadcasts.

xs = [1, 2, 3]

function ff(x)

if x < 2

3

else

5

end

end

ff.(xs) # => [3, 5, 5]

For normal Julia arrays, . may perform CPU parallel accelerations.

For JuliaGPU’s CuArrays, . performs GPU parallel accelerations.

The last reason I’d give here to convince Julia is a good codegen target is, you can access many native stuffs, you can target LLVM IR/native ASM by target Julia.

This is an example for directly calling LLVM IR from a Julia developer:

@inline function assume(v::Bool)

Base.llvmcall(("declare void @llvm.assume(i1)",

"""

%v = trunc i8 %0 to i1

call void @llvm.assume(i1 %v)

ret void

"""), Cvoid, Tuple{Bool}, v)

end

We can also use the C wrapper LLVM.jl to access those most commonly used LLVM APIs.

Generating native assemblies and calling them are also relatively easy in Julia, here is A REPO for generating x86 ASM with Julia.

Julia can help you get rid of those tedious parts when working with complex things like LLVM or ASM environments, and help us researchers to focus on code generation itself and achieving functionalities.